The Richard Wall House, circa 1682. Source: Eric and Noelle Grunwald.

We have a devote Quaker to thank for the oldest stone home in Pennsylvania. Richard Wall came to America in the mid-summer of 1682, after purchasing 600 acres of land directly from William Penn. His land grant, along with 13 others, came to form Cheltenham Township, named after Cheltenham, England.

Wall’s home, coined “The Ivy” for the series of vines that once climbed its stone walls, certainly played its part in the early history of America. The humble Elkins Park abode served as one of the earliest Quaker meeting houses (and wedding/reception site for families within the congregation) and, later, a very important stop along the Underground Railroad.

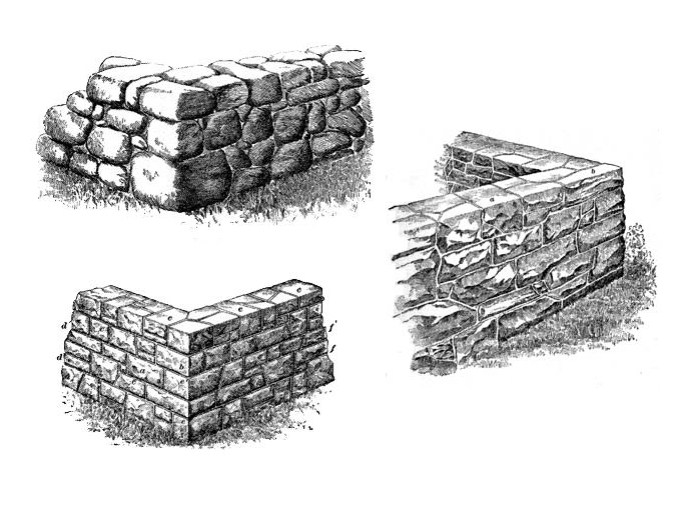

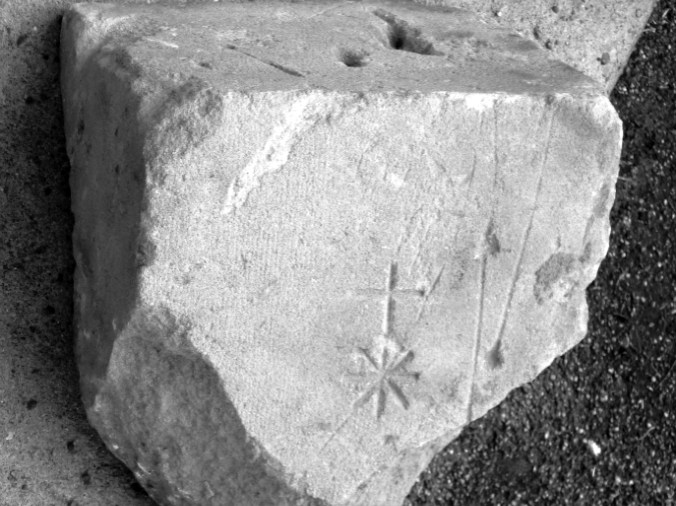

And like most old stone homes in the states, the Wall House was a work in progress – at least for the first 245 years of its life. In 1682, shortly after arrival in Pennsylvania, Richard Wall built an 18’ x 30’ two-story log cabin with grey fieldstone end and fireplace. This style was in keeping with William Penn’s own suggestions on home style and construction and adapted from methods learned by the first wave of Quakers who migrated to New England during the 1650s-1670s and brought the building style back with them to England. (See our feature on construction method by region; New England stone enders). Subsequent tweaks and additions to the home came in 1730, 1760, 1760-1790 (when the log portion was removed), 1805, 1860 and 1927.

The original portion of the Richard Wall Home, constructed in 1682, may have looked quite similar to John Wormley’s family home, a circa-1769 log cabin located in Camp Hill, Pennsylvania.

After serving as the residence of four families, the property was purchased by Cheltenham Township in 1932 and served as the home of township managers. In 1980, the Cheltenham Township Historical Commission took the property under its wing and today operates a museum of local history at the site.

Resources:

Richard Wall House Museum

Restoration Offers House Historic Future by Rhonda Goodman