Three properties popped up in the news this week: one in desperate need of repair and two others of historic significance. Let’s take a look.

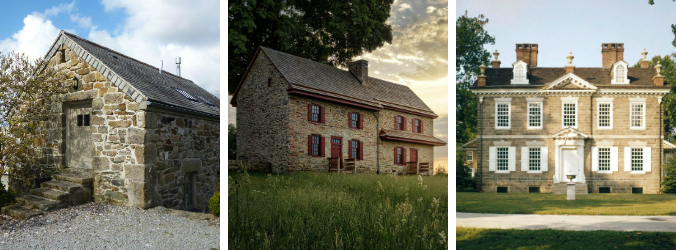

A Stone Home in Danger

The Lapole House (Lurman House) in Catonsville, Maryland, may not look like much at first glance. The boarded-up stone cottage is located on the grounds of Catonsville High School but was once part of a much larger estate. The story starts with Edward Dorsey, who gave the name “Farmlands” to the area in the late 1700s. He passed the large tract of land to his son, Hammond, who built a mansion on the site in the 1790s. In 1820 the house with six hundred acres was sold to Henry Sommerville, who renamed it “Bloomsbury Farm”. In 1848, Gustav W. Lurman, Sr. purchased the estate and restored its original name. The Farmlands estate passed down through the Lurman family until 1948 when Miss Frances D. Lurman sold the last 65 acres to the Board of Education. The main house and most outbuildings were demolished in 1952 to make way for the high school. The tenant or gardener’s cottage, once the home of estate caretakers Charles and Ida Mae Lapole, is all that remains today. Local resident Jim Jones is raising awareness in hopes that the cottage can be saved from the ravages of time, weather and vandalism.

A Stone Home That Needs an Owner

It’s a mansion in fine condition. The only thing lacking is an owner. And for $3.7 million the home could be yours! Located in Fieldston, a privately owned neighborhood in the Riverdale section of the northwestern part of the Bronx, this 100-year-old home of solid fieldstone construction features eight spacious bedrooms, 5.5 bathrooms, a formal dining room and a renovated eat-in kitchen. The Craftsman-style home, designed by architect William B. Claflin and built for Columbia University professor George B. Pegram, sits at the top of a 1/2-acre sloping, terraced lot and exists within the Fieldston Historic District.

A Stone Home That Wants to Tell Its Story

The 900-square-foot home at 617 Ash Street in Boise, Idaho, was once surrounded by timber-framed homes in a bustling neighborhood coined River Street. Built in 1907 of sandstone, the house became home to Erma Andre Madry Hayman and her husband Lawrence in 1943. Erma raised a large family in the small home and lived to the ripe old age of 102. After her death in 2009, grandson Richard Madry sold the house and property to the Capital City Development Corporation. Hopes are to protect the home via a National Trust for Historic Preservation designation and learn more about the vibrant multicultural working class community via an archeological dig at the homesite, led by the University of Idaho field school.

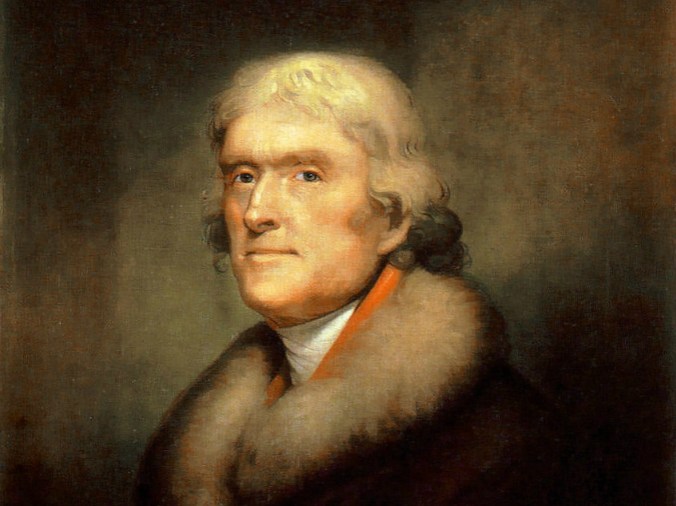

Thus emerged the “Adam” style, made famous by Scottish architects Robert and James Adam, brothers who designed large country estates in England, circa 1750- 1800. Once word spread to our side of the pond, the name was surreptitiously changed to “Federal” and a truly American architectural form was born.

Thus emerged the “Adam” style, made famous by Scottish architects Robert and James Adam, brothers who designed large country estates in England, circa 1750- 1800. Once word spread to our side of the pond, the name was surreptitiously changed to “Federal” and a truly American architectural form was born.