Saving old buildings seems a struggle, a tug of war between individuals who seek to preserve our heritage and those in charge of the structure, the land it sits on … or the purse strings.

Right now, two stone structures are at risk as groups involved in their care work to reach compromise.

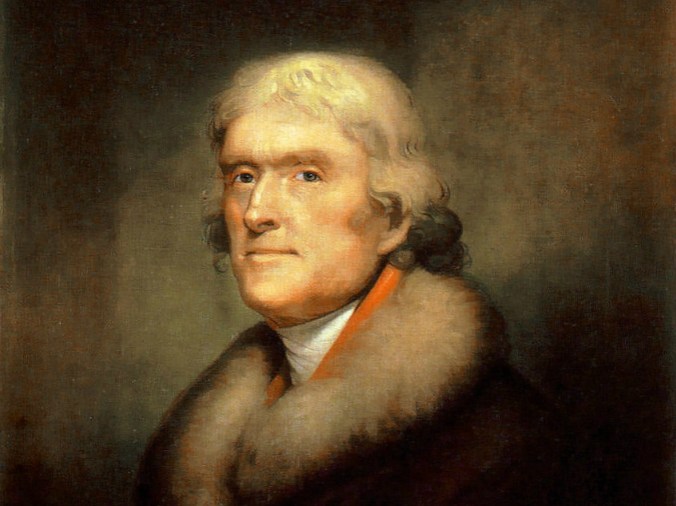

The Steuben House in River Edge, New Jersey, is an excellent example of Dutch colonial style. The sandstone structure served as General George Washington’s headquarters in 1780. Source: Ken Lund.

The Steuben House, located at Historic New Bridge Landing in River Edge, New Jersey, is a Revolutionary War landmark, as it witnessed an important retreat from British forces led by Gen. George Washington on November 20, 1776, and also served as Washington’s headquarters for a time in 1780. The sandstone building, an excellent example of Dutch colonial architecture, is long overdue for repairs; talks are ongoing amongst parties involved: the Bergen County Historical Society, the state of New Jersey and the Department of Environmental Protection. Difficulty in raising funds to make repairs and improvements and disputes over types of improvements that can be made at the park have delayed progress.

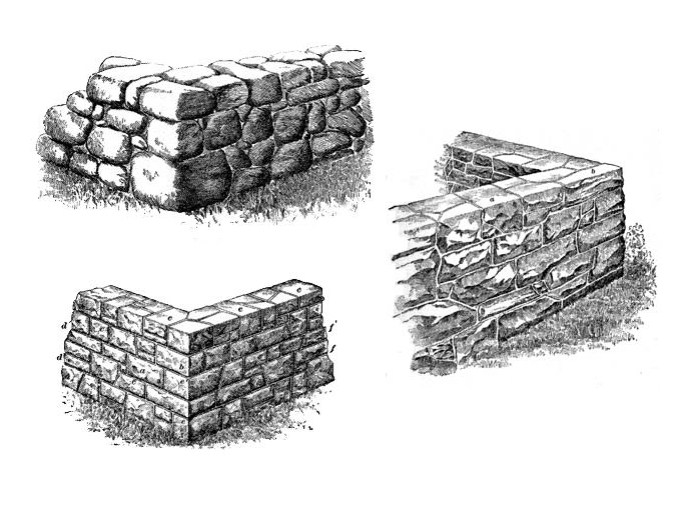

The Newburgh Dutch Reformed Church is a fine example of Greek Revival style. The endangered fieldstone building needs a new roof. Source: Abandonedhudsonvalley.com.

A New York state historic site in desperate need of TLC, the former Newburgh Dutch Reformed Church is an outstanding example of Greek Revival style. The church, designed by famed American architect Alexander Jackson Davis, was built in 1838 on a hill overlooking the Hudson River. The structure, reminiscent of the ancient Greek temple at Illissos, rests on a five-foot-high podium, features four 37-foot-tall columns and fieldstone walls that were once covered in stucco and painted to resemble stone. In recent years, wall and ceiling collapses have left the building vulnerable to decay and vandalism. Funds to stabilize a failing roof are desperately needed; the city of Newburgh and the Newburgh Preservation Association have reached out to Newburgh’s Community Land Bank for assistance.

Do you know of a historic stone structure that can’t seem to catch a break? Share with us!