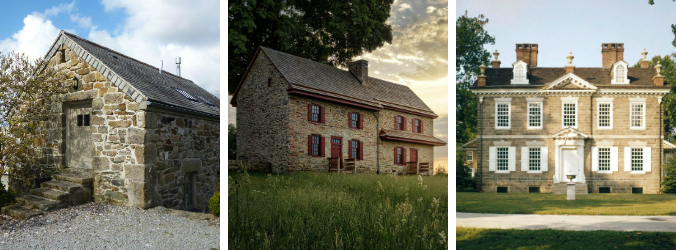

You know those two-story, take-your-breath-away stone homes you sometimes find closer to city centers and clearly built by skilled tradesmen? Congrats! You’ve just happened upon a Georgian-style home. Why significant? Early American stone homes called upon regional folk styles and were often built by owners themselves. By the 18th century, we had established ourselves in this country and had amassed enough wealth to build more formal, refined structures.

The Georgian style in America made its way here from England, where classical forms of the earlier Italian Renaissance period were popular. Hallmarks of this home style included:

The Georgian style (1700-1780) gave way to the Federal style after the American Revolution. Cliveden (Benjamin Chew House, shown above), located in Germantown, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, is a fine example of Georgian style. The mansion was in part designed by its owner Benjamin Chew, a successful Philadelphia lawyer, and built by Mennonite master carpenter Jacob Knor, mason John Hesser and stonecutter Casper Geyer. The home takes inspiration from Kew Palace as well as patterns in James Gibbs’s Book of Architecture. An ashlar front of gray Wissahickon schist (the predominant bedrock underlying Philadelphia) and gable ends and back of rubble construction are outstanding features.

Could you see yourself as the master of a grand Georgian estate? Take our stone home personality quiz to find the home style that’s right for you.

References:

Cliveden: The Building of a Philadelphia Countryseat, 1763-1767

Common Building Types: Houses, schools, courthouses